Smiting Will Ensue: a Q&A with Carol Pal on Kenneth Burke’s “On the First Three Chapters of Genesis”

Bennington faculty member Carol Pal

Kenneth Burke was a literary theorist, philosopher, and professor at Bennington College. He taught at the college for twenty years, between 1942 and 1962. The Crossett Library archives reveal that at Bennington, Kenneth Burke gave a lecture on his essay “On the First Three Chapters of Genesis” (published in his highly influential book, The Rhetoric of Religion in 1961). In this essay, Burke uses a logological lens to view the text; logology is the study of language and symbols. Essentially, this essay is one of his many writings that claims humans organize their thoughts, societies, and beliefs based on hierarchies.

I sat down with historian and current Bennington faculty member Carol Pal, who regularly teaches a course on Genesis. Together, we tried to make sense of Burke’s dense essay.

Literary Bennington: In his introduction, Kenneth Burke talks about taking a “logological” approach to reading Genesis. He identifies three major themes—Creation, Covenant, and the Fall—and claims they can all be derived from language. One of his examples is Order implies a God figure, because someone had to have created order. Or at least that’s what I think he’s saying. How do you interpret what he’s saying, and what do you make of it?

Carol Pal: Alright. I’m just a historian here. I see the beauty of it, that the themes of the narrative itself are in here, in the actual words, so that you can look through the words used or so you can see the deployment of certain terms and see the themes of the book as a whole. I saw that, I saw the appeal of it, but [laughs], for me, in terms of understanding the book itself, I think it’s just crap. [Laughs] I know I’m talking about this total genius God of literary studies, but it has nothing to do with how the book was actually written.

What I don’t get is that since at least the beginning of the nineteenth century, there’s been the Documentary Hypothesis, the belief that this is all these different voices; there was a J, a P, an E—and unless you adhere to a literalist view of the Bible, where you think it’s actually the word of God, so either God wrote it or dictated it and Moses wrote the first Five Books—even though he died before the end which requires explanation—unless that is your viewpoint, you have to think it was written by a human beings who aren’t like magic Moses. Then, it’s just about impossible to avoid the Documentary Hypothesis, which is that this is all different narratives. So, how can you simultaneously know this about the Bible—that it was just mashed together from all these different things and then edited by successive generations of scholars and theologians until it got to the form we have it in today—how can you simultaneously know that and make the argument for authorial intention?

LB: That’s a great question. I wish Kenneth Burke was around so we could ask him.

CP: So do I. I wish we could do a debate. I mean, I’m sure he’d crush me, but I want to ask him.

Kit Foster’s diagram of Burke’s lecture from the Crossett Library archives

LB: What do you think the value is of approaching the text this way? From this literalist, logological perspective?

CP: To me, it strikes me as a very clever game, so I’m not sure what the purpose is of the game. I understand, if he were talking about another book that actually had an author, then I would say this is not only very smart, but very useful. If you take the position that the first five books of the Bible are about establishing God’s commands for the Hebrew people, which is a very rabbinical view of the first five books of the Bible—if it’s about God’s laws for the Hebrew people and how they developed, another word for that would be order. And if you could see if it’s about order, and it’s also narratively—all the words and the constructions—moved towards creating a sense of order, so it’s not only the content but also the style—the employment of words, the choice, the structure—that is very clever. And I would go with it, if it weren’t this book, which we know is not… Unless he’s a literalist, which I would like to ask him: So, do you think God wrote this? Moses? If not, how can you do this?

Because to me, that just defies logic, and the only thing I can think is either a) he doesn’t believe the Documentary Hypothesis and this is perfectly straightforward, or b) he does, and he’s just having fun here. And that to me seems a little irresponsible because it is kind of a book that millions of people have died about. So, you want to be careful to pretend, perhaps, that you can read authorial intention because if you don’t actually believe it had a single author, then why write something that kind of implies it does? This, to me, is playing with dynamite. Because it is the Bible. Because much blood has been shed.

LB: How does your reading on the first three books of Genesis differ? Are there any themes in the text that you would pick out that are different from the ones Kenneth Burke identifies?

CP: In our class, we kind of identified this as God’s learning curve. Like he was a teen dad or something and just couldn’t figure out what to do with this thing that he made. Who are these guys, and why do they keep messing up, and what am I supposed to do with them now? The God in the first three books of Genesis messes up hugely. So, why is this stuff in there? I have no one particular idea about that. I think it’s a great story. The action is amazing. It’s moving, it’s funny, the visuals are intense, and it also would be super familiar to everyone in the area because it borrowed so much from Babylonian myths, like the Gilgamesh flood narrative. It’s so resonant with all the other cultures, not just the Hebrews. Acadians, Babylonians. So it would be a story that everyone was familiar with, and it would be a great thing to sit around at night and tell this story, and it would also tell you why your tribe and your God is better than all the other tribes and all the other Gods. So, to me, it’s about storytelling. It has anthropological justifications. Everybody’s got a story of who we are as people. Where did we come from? Why are our gods better than other people’s gods? No Redeemer.

He talks about sacrifice in terms of Redemption. I don’t know. It strikes me that all we learn that sacrifice is that we just learn that God really likes meat. [Laughs] What’s the Cain and Abel story? Oh, you gave me vegetables… WRONG. I like meat! Smite.

So I think it’s a great story, it’s a familiar story, and it’s a useful story. That’s what I think. And while this book is all holes with little bits of narrative stitching it together, the one thing you cannot fill the holes with is Jesus. Not in Genesis. You can fill those holes with a lot of things, but not Jesus. That’s what I’m telling you, Kenneth Burke.

This is Jewish. It’s about the Hebrew people, but he keeps reading Christian stuff in there. The idea of Redemption. And he says this: the idea of Redemption implies a Redeemer, and he looks at the binding of Isaac as that. That is a particular reading that just kind of erases the Jews. It says this is all just getting ready for Jesus. The entire Old Testament is getting ready for Jesus. And Jews don’t have a Redeemer, so he’s also not owning that he’s putting a Christian-centric template onto the Old Testament. I wanted to shake him over that. This is the Jews! Ain’t no Redeemer! They’re Jews! That’s Christianity co-opting the Jewish narrative and co-opting everything that happened to the Hebrews as getting ready for Jesus. Seeing the Hebrews as not people on their own merits but as pre-Christians, which is very colonizing. It’s sad to see somebody with this level of intellect doing that because I see that as disrespectful.

LB: It strips these people of their identity and place in history.

CP: And it’s also just factually unhistorical. There was no Jesus. But I’m a historian. I believe events unfold in time. A lot of Biblical interpretation does not acknowledge events unfolding in time. There’s kind of this magical time. I will grant people narratives and magical time—that’s why we have fiction. But fictions have writers. Authors. And we’re back at this: there is no single writer. Am I doing enough raving here?

LB: This is great. Is there anything else you want to rave about?

CP: I’ll just say another thing I want to strangle him over: he starts talking about—and I don’t know if this is for his Hebrew street cred or something—but after he’s talked about a Redeemer, he starts talking about Rashi, which is this rabbinical interpreter of the Bible, and super, super influential still today. And talking about how Rashi writes about Genesis, which is fascinating but Rashi was writing in the eleventh century. So when he’s going on and on about a theory that sees the real Bible starting with Exodus and God giving the law to the Hebrew people, that it’s really about the law, and there is no law actually in Genesis, so all of Genesis is actually a precursor to the real beginning of things, that’s very interesting. But the point is that Rashi was an eleventh century scholar, and he was really interested in the scholastic-scientific debates of his time and he really wanted to get into this conversation about which of the four elements was the first and the most important: earth, air, fire, water. And his chosen horse that he was betting on was water. He was also perhaps playing games with the text and wanted to show how Genesis was, in many ways, about water, about the heavens, about the formless earth before things were separated. But that’s not in here. He just says, “Rashi says…”

LB: You very much stress that he was writing in the eleventh century, and I was going to ask: have you noticed any trends in terms of what’s being said in the academic world about Genesis, and whether or not the time and historical context that something is being published in affects what’s being said?

CP: It completely shapes what’s being said. We’re talking about a text that is, depending on which part of it you’re looking at, is two and a half millennia old, right? So it is not unchanging word. I mean, that’s Biblical literalism—the unchanging word of God. But it isn’t. So it’s completely shaped by every person who reads it and every set of questions that’s being asked. So, Rashi was asking a set of questions pertinent to the eleventh century.

LB: What are the questions that Burke is trying to answer for the people of his time?

CP: I suspect it has a lot to do with academic fashions. What people are thinking. Literary criticism goes through fashion cycles, as does historical analysis. Actually, that’d be a question for someone in the lit area. Is there a field of criticism in the ‘50s and ‘60s to which this belongs? My guess is yes; I’m just ignorant about it. I have no idea. The nineteen hundreds was my least favorite century. Trash it. It just left everything very cut and dried. It was very much about categorizing human beings.

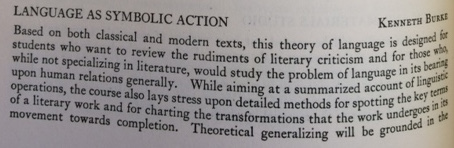

From the bound curriculum books in Crossett Library (1954)

LB: Let’s talk about the present day. Leave the 1950s. Leave Kenneth Burke. What are the trends right now in terms of what we talk about when we talk about Genesis?

CP: Biblical criticism? This is completely shaped because biblical criticism is not my tippy-top thing that I do. I approach it as a) a historian and b) a historian of the book. So when I talk to people about the Bible, we’re all thinking about it as a book and thinking about the ways in which it came together and was edited and re-edited and translated and interpreted. Those are the people I hang with. Because I’m not hanging with the Biblical literalists. I just hang with other people who see it as a book that’s put to religious uses but that is a cultural creation. Put together by Hebrews, for Hebrews. Adapted by Christians, for Christians. That’s how I see it.

By Katie Yee ‘17