Bret Easton Ellis ‘86 on Past Work, Visual Art, and Brevity

Bennington faculty members Arturo Vivante and Mary Ruefle sign off on Bret Easton Ellis’s literature thesis, the short story collection This Term’s Model

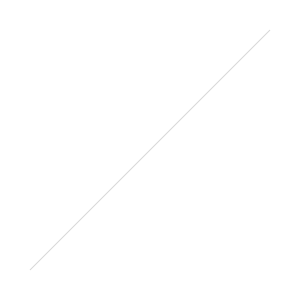

This past week, Bret Easton Ellis (class of ‘86) discussed something with Literary Bennington that we all fear ever having to revisit: our undergraduate work. In our previous discussion last fall, Ellis granted Literary Bennington permission to see his undergraduate literature thesis, which until then had been placed off-limits. The vintage graphics from Spy Magazine below show just how much interest there was in Ellis’s thesis among the literati in New York.

It didn’t take us long to discover that practically all of the stories in Ellis’s thesis had been published in some form, whether in his 1994 story collection The Informers, or his 2005 novel Luna Park. Only one story in the collection remains unpublished. The title story of the thesis, “This Term’s Model,’ is a 37-page short story that explores the relativity of sex and gender at Camden College in 1984. The undetermined gender of its narrator anticipates similar experiments in fiction by Jeanette Winterson and others.

Ellis opened up to Literary Bennington in this phone interview about the past and future of this hidden gem, as well as the recent opening of American Psycho: the Musical on Broadway and his collaboration with visual artist Alex Israel at the Gagosian Gallery in Los Angeles.

Literary Bennington: Thank you so much for taking the time to talk with me and allowing me to read your thesis, This Term’s Model. Not every Bennington author gives students access.

Bret Easton Ellis: I haven’t looked at my thesis since I turned it in. I can’t bear to read anything that I’ve written more than a year old. Though I think there are stories in there that I rewrote and published in The Informers.

LB: All of the stories took some other form outside of the thesis, whether in the The Informers or other books of yours. Except the title story, “This Term’s Model.” Why did this one get left behind?

BEE: I remember I wanted to put “This Term’s Model” in The Informers and I had a long talk about it with my editor at Knopf at the time. It was his suggestion that we do a book of short stories because it was going to be a long time between my last novel and the one I was working on. I gave him the thirteen or fourteen stories that I wanted to put in. He felt, I remember at the time, that all of the stories were L.A based. Even if the characters ween’t in L.A, they were from L.A. I thought it would be fine to have “This Year’s Model” in the middle of the book. There are a couple of stories that are connected to Camden College. He argued persuasively that no, it didn’t fit thematically with the rest of the collection. We talked about it a lot and I finally agreed.

I’ve always thought about revisiting that story. I remember the idea came from having a narrator you didn’t know the sex of …

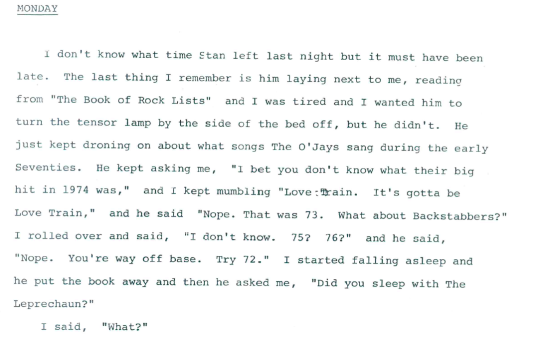

The opening of Bret Easton Ellis’s unpublished short story “The Term’s Model”

LB: That’s the exact question I had on my mind while I was reading the story. I still can’t figure out which gender the protagonist is..

BEE: That was the idea in writing the story. The idea was a week in a life of this person, in this world. It was supposed to be about does it matter? Does gender matter when it comes to a story like this? It seemed important to me at the time. This could be a girl or this could be a guy and, for some reason, the fact that we don’t know or it wasn’t said was the point.

The story was supposed to engage the reader in terms of their presupposed ideas. “Oh it has to be a guy because of this, this and this. Or no, maybe it has to be a girl because of this, this, and this.” I thought, at that moment, that I didn’t necessarily see gender that way.

I feel differently now, actually. I do think there are gender based differences that do define who we are. This was a short story, it was an idea.

An “expose” from Spy Magazine showing Ellis’s thesis to be the source of many of the stories in his 1994 collection The Informers

LB: It is interesting that the sex and gender is so ambiguous, but you make so many direct references to houses and specific people on the Bennington campus. Was there any backlash at the time?

BEE: It was one of the only stories of mine that I really didn’t show anyone. By the time it was in thesis, I was out of there as a writer. It was never shown it anybody. It was the last story I had written and it was not shared publicly.

LB: But you are thinking of revisiting it?

BEE: Yeah. It’s kind of interesting how it’s a time capsule, in a way. This is what it was like a hundred years ago. I always like to mess around with the idea of sex and gender. I started doing it in Less Than Zero, this idea of heteronormative behavior. I remember that Less Than Zero seemed so shocking to so many people when, 25 pages in, you realize that our narrator is bisexual. I just thought this is my idea for a character and I didn’t think it would be such a “whoa” moment. It’s in there so casually. He didn’t even comment on his sexuality; he just sleeps with whoever he sleeps with. That’s always interested me. I think coming from a place where I felt okay with my sexuality, I was never anguished over it, I never politicized it, it never became a big thing. And for other people it’s fine that they did. For some reason, just because of my make-up, I just didn’t. I wasn’t that person. I always think about revisiting “This Term’s Model” and putting it out there.

LB: I mean you’re so busy with other stuff I understand why you might not have the time.

BEE: Not necessarily. It’s sitting in my closet five-feet away from me in a file. I could easily go over, look it up, I know exactly where it is. The problem was my old editor thought it was boring. He thought it didn’t build to anything, which I disagreed with. I just wanted to get the day by day by day feeling of what the life of a student was like and I didn’t find it boring. I like that type of writing. I like the daily incident and that the story is not so plot heavy. A reader is allowed to read it and take from it what they want. He had edited famous short story writers who wrote in a very classic way. He had a lot of problems with my stories in terms of that. In terms of like describing life and not being that concerned with plot. He wanted something more forcefully dramatic and also where there is an epiphany. And I think there is.

LB: You said earlier that you don’t like to revisit your earlier work. And yet there are so many different adaptations going on. The musical version of American Psycho just opened on Broadway.

BEE: It’s done when it’s done and then it goes out into the world. You feel it’s finished at a certain point. Then it’s published. The problem is when you go back you want to change things. There’s always the editor working in your mind. You wished you used another word, you wish you had cut that line, you wish you had ended that section differently. It is an annoyance and a distraction and that’s why I can’t reread the stuff that’s been published. And that goes for every book I’ve written. And I’m going to have to if the Lunar Park movie goes through and I write the script [note: a film version of Ellis’s 2005 novel Lunar Park is in development]. I’m going to have to reread it. I had to reread American Psycho when I was working on Lunar Park, which was a very difficult thing to do. I wanted to read the entire novel and I hadn’t looked at it since it had been published. It’s like, uh that’s not what I would do now.

I remember I was signing a copy of Less Than Zero for someone and I flipped through it a little bit and said to myself “Oof, not that, not that.” It’s only in my mind, the reader doesn’t know that. The reader is just reading the book and taking from it what they want. It’s harder for the writer.

LB: What are your thoughts on brevity as a whole? How do you approach shorter works compared to longer ones? I ask this in regards to the single sentences that were paired with Alex Israel’s stock images in your recent show at the Gagosian, as well as your reputation for having such a huge Twitter following.

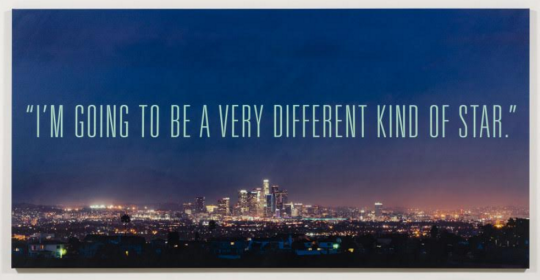

Different Kind of Star, one of the works from Alex Israel and Bret Easton Ellis’s collaboration for the Gagosian Gallery in L.A.

BEE: The Gagosian project came about because Alex Israel was a fan of my work and we met and became friends. He suggested a collaboration and told me to just start writing sentences and set them around Los Angeles. Maybe young people, maybe they’re driving to the beach. Very banal things. Not a chapter from a novel, not first sentences: just ideas, sentences. He wanted me to construct them in way that we’re wondering what’s going on around them and what’s going to happen after the line is over. Give them a little bit of suspense and make the reader get a sense of what this person’s life is like. This was an idea we kept fooling with for about a year, and he was also looking at the imagery he wanted to put the sentences with.

It was a very long process. I would write the lines to specifications, I would move one name to another sentence, I would move one text to another image, until we finally got 18 finished for the Gagosian show. We have another 18 ready for another Gagosian show that will be in London next year. The same world, the same kind of images. The idea of brevity to a degree has interested me…not brevity, a kind of simplicity or directness. I have books that aren’t short and I have written run-on sentences. Tell me again what you mean by brevity?

LB: Sort of how the concept of the “one-liner” has functioned in your work, past and present.

BEE: Well, I’ve never written like that before. I’ve always written a short story or a book so writing these lines of text hard because it was unlike any other kind of writing. We were definitely thinking of imagery. We were writing them and asking, “What are you thinking about? What do you think of this text?” We called them “texts.” I would say I see the Pacific Coast Highway over near Malibu, maybe it’s foggy, maybe there’s a girl… and Alex would say, “Well, I don’t really want to do a face.” Then we would talk about it. And he would say, “Wouldn’t it be cooler if it was just an empty apartment overlooking the city?” and I would say, “That could be it too.” That’s how the conversations would go. The texts really had to serve the visual.

A billboard for Israel and Ellis’s show at the Gagosian Gallery in L.A. It closes on April 23rd

LB: I know Bennington was and is a very visual/dramatic arts focused school. Did that have effect on your writing? You make a number of references to visual art in the stories in your thesis, including in “This Term’s Model.” Was it this interest that ultimately brought you to do this collaboration?

BEE: This is the first collaboration I’ve ever done and probably the only one I’ll ever do. I really do think if you were born at a certain point in the 20th century that movie and films have an influence on every prose writer that came after the rise of film. You can even see it in The Great Gatsby and some of Hemingway. You can really see when the cinematic vocabulary began to change American Fiction. I definitely was writing Less Than Zero while being influenced by the movies at the time. Less so as I became sure of what I wanted to do with the novel. But sure, being influenced by that kind of visual art was a huge thing. Also, just writing screenplays.

You know, a movie isn’t a script. That is a big mistake people often make. The script isn’t the movie, the movie isn’t the script. Any time a screenwriter gets blamed or wins an award for a film it’s kind of crazy for anyone who works in movies. Film is a director’s medium. T.V and theater are different, but film is where the director is the auteur and not the screenwriter because it changes so much.

LB: So you don’t think you would do this type of collaboration again?

BEE: I don’t know. The idea behind the show is that there aren’t many of them so they’re worth something. Collectors bought these because there are only eighteen of them, not because there were a hundred. That would have really been a different situation. So I don’t know, if somebody asks me, maybe?

It was interesting to see a part of how the corporate art world works. The Gagosian is a huge gallery. It’s not like you’re showing at the Ethel and Fred Gallery. It’s a corporation. And the art reflects it to a degree. I mean these are giant paintings, they’re massive, and as a collector you have to have space to store it, or to hang it. It was a whole inside look at how that whole world works.