The Slaughterhouse Commencement (1970)

Image courtesy of Crossett Library’s digital archive

A year after the 1969 release of his hit novel Slaughterhouse-Five, and at the height of the Vietnam war, Kurt Vonnegut came to Bennington College to give the Commencement Address. In a move unlikely to surprise any of his readers, Vonnegut employed his usual level of satire and dark irony to convey a largely anti-war message to the bright-eyed graduates of the Class of 1970 and their families.

One of the first lines of Vonnegut’s speech argues for the need of a greater military presence on campus (Bennington, mind you, didn’t even have a single sports team at the time):

I demand that the administration of Bennington College establish an R.O.T.C. unit here. It is imperative that we learn more about military men, since they have so much of our money and power now. It is a great mistake to drive military men from college campuses and into ghettos like Fort Benning and Fort Bragg. Make them do what they do so proudly in the midst of men and women who are educated.

Vonnegut’s trademark quips highlight the fact that, during the military buildup of the time, spending on weaponry, training, and overseas deployments were rapidly accelerating. Fort Benning and Fort Bragg were certainly not ghettos, unless you consider an annual defense budget of $406 billion (more than $900 billion in current dollars) “ghetto.” The beauty of Vonnegut’s address to the graduating class that year lies in his deft use of satire rather than a pleading call to action. “There is a lesson for all of us in machine guns and tanks,” Vonnegut blustered to his audience, sounding an awful lot like Stephen Colbert: “Work within the system.” There is no denying the dark underlying truth: American democracy was in crisis.

Just as he doesn’t spare the military industrial complex, Vonnegut goes on to bash the arts. But this time, he shows his hand.

Which brings us to the arts, whose purpose…is to use fraud in order to make human beings seem more wonderful than they really are. Dancers show us human beings who move much more gracefully than human beings really move. Films and books and plays show us people talking much more entertainingly than people really talk, make paltry human enterprises seem important. Singers and musicians show us human beings making sounds far more lovely than human beings really make. Architects give us temples in which something marvelous is obviously going on. Actually, practically nothing is going on inside. And on and on.

I get the impression from the speech that the arts are the only thing that actually matter to Vonnegut. But then again…it’s Vonnegut. So who can tell? Perhaps the only thing that really matters to him is the comfort of nihilistic despair.

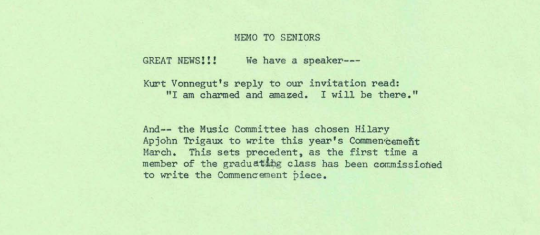

From Bennington’s Commencement Program in 1970

Vonnegut’s pointedly duplicitous speech from 1970 isn’t the most graceful commencement address you’ll ever read, but it certainly came at the right time—as a class of ready and willing graduates were just about to leave the Bennington nest. Bird-like, out into a world of insatiable greed, of cruelty, of death. The moment of ringing truth? Ironically, it comes when Vonnegut quotes Shakespeare’s Henry VI: “To weep is to make less the depth of grief.” To weep is to make less the depth of grief. Let it sink in. “It is from the same play, which has been such a comfort to me, that we find the line, ‘The smallest worm will turn being trodden on.’ I don’t have to tell you that the line is spoken by Lord Clifford in Scene One of Act Two. This is meant to be optimistic, I think, but I have to tell you that a worm can be stepped on in such a way that it can’t possibly turn after you remove your foot.”

This passage must have resonated then, at the height of a gruesome war, and perhaps it will again today in the age of #BlackLivesMatter and rising inequality. Vonnegut’s dark, backwards call to action might again be employed to the potential escalation of our current political…uncertainty.

Vonnegut closes his address with a rant about the Free Enterprise and an outright plead for socialism, which is where his writing unravels a bit. So instead, I’ll leave you with one of his final thoughts before his closing economic diatribe.

I know that millions of dollars have been spent to produce this splendid graduating class, and that the main hope of your teachers was, once they got through with you, that you would no longer be superstitious. I’m sorry—I have to undo that now. I beg you to believe in the most ridiculous superstition of all: that humanity is at the center of the universe, the fulfiller or the frustrator of the grandest dreams of God Almighty. If you can believe that, and make others believe it, then there might be hope for us. Human beings might stop treating each other like garbage, might begin to treasure and protect each other instead. Then it might be all right to have babies again.

If only David Foster Wallace, Vonnegut’s logical successor, were around to deliver this year’s commencement speech. I’m sure there would be several Trump references in conjunction with crustaceans.

Read Vonnegut’s full address here.