Nothing Too Small: Poet Mary Oliver at 80

When I was in high school, the wife of my father’s friend asked me if I had ever heard of Mary Oliver, knowing how much I loved to read and write poetry. When I said I hadn’t, she recited “Wild Geese,” her favorite poem of Oliver’s. “You do not have to be good,” it starts. “You do not have to walk on your knees / for a hundred miles through the desert, repenting. / You only have to let the soft animal of your body / love what it loves.”

That kind of affirming, gentle magic was what I began to fall in love with as I read A Thousand Mornings and Why I Wake Early: New Poems, two collections of Oliver’s that the same wife lent me that summer. I remember sitting by a lake, surrounded by the buzzing greenery of Vermont, a perfect place to take in Oliver’s reverent love of nature. (In fact, Oliver taught here at Bennington from 1996-2001, exploring Frost, Poe, and different facets of poetry writing with her students). I was touched by her celebration of little things, like crickets and sparrows, calmed by her calmness, and awed at the way she might drop a simple though profound truth at the end of a poem. So naturally, I was excited to discover that a new book of Oliver’ poems, Felicity, was coming out in October. She is 80 now, and I wondered how I would find her work after not reading it for so long, and how, at this point in her life, it might have changed.

Flipping through the volume, I was hoping to find the same timeless magic in her poetry as I’d seen in earlier books, but I was surprised to find that she has stepped away from nature in her work to decidedly refer to more human things. In “Roses,” she brings up kissing, going to the mall, and the Super Bowl as a flurry of human actions that, despite their constant motion, cannot stop death. In fact, she has a whole section of the book titled “Love,” about the joys of seeking refuge in another person. Though Oliver’s poetry isn’t usually populated with other people, this section seems to be filled with a presence of someone who is loved. It is a joyous, celebratory and healing section to read–in reading it, I couldn’t help but wonder whether the struggles of her life, such as her bad childhood, poverty and isolation, were present as undercurrents. Although I hadn’t seen poetry about love in her past books, I smiled at the thought of things human love can give us that nature cannot, and that those discoveries and revelations are present in her poetry. In fact, in “Except for the Body,” Oliver compares nature with love, and concludes that between the two, “the trees would come in/an extremely distant second.”

Poet Mary Oliver. Photo by Angel Valentin for The New York Times

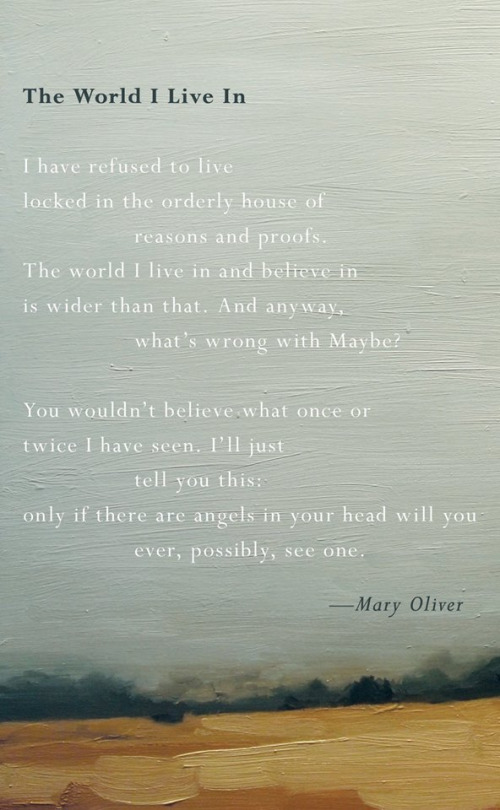

These shifts in subject matter, though surprising, do not shake the core of her writing. As a matter of fact, in the beginning of the book Oliver seems a bit over-reliant on her plain, colloquial tone, while many of the poems themselves do not have enough substance to meet the plainness with any kind of merited power. That does not mean that Felicity is devoid of beauty or joy. Two poems stand out to me: “The World I Live In” and “Nothing is Too Small Not to Be Wondered About.” In the former, Oliver writes with the confident certainty I’ve been familiar with in her other books–a conviction to tell us what she knows and has learned about the world. The ending resonates:

only if there are angels in your head will you

ever, possibly, see one.

It is in endings like this that make me feel as if there is more to the world I have yet to discover. In “Nothing is Too Small Not to Be Wondered About,” Oliver has a miraculous way of making my heart ache so much for a dying cricket, which in its end, deserves as much in its little death as any other being. It is poems like these that show how Mary Oliver can still write with grace, and still has the uncanny ability to reveal, in one small poem, just how vast and wide the world can be. Felicity may be more of a collection of hit-or-miss poems, but the poems that shine, shine: they soothe us, teach us, inspire us, and take our breath away.