Fetish Objects: a Banned Book by Henry Miller

Henry Miller and his lover Anaïs Nin in 1932

In the third installment of Fetish Objects, Glenn Horowitz, the renowned Manhattan rare-book dealer (and Bennington class of ‘77), sheds light on a typescript of Henry Miller’s 1936 novel Black Spring. This book, along with Miller’s Tropic of Cancer, Tropic of Capricorn, and the famous Rosy Crucifixion trilogy, was banned in the United States until 1961, and it greatly helped build Miller’s underground reputation.

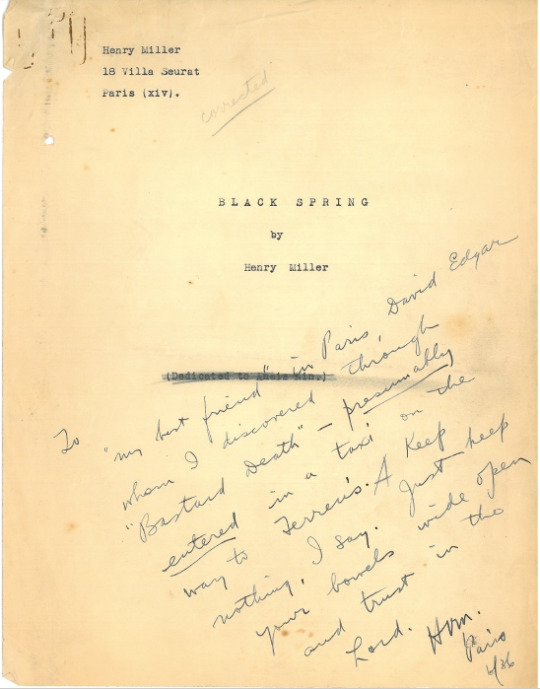

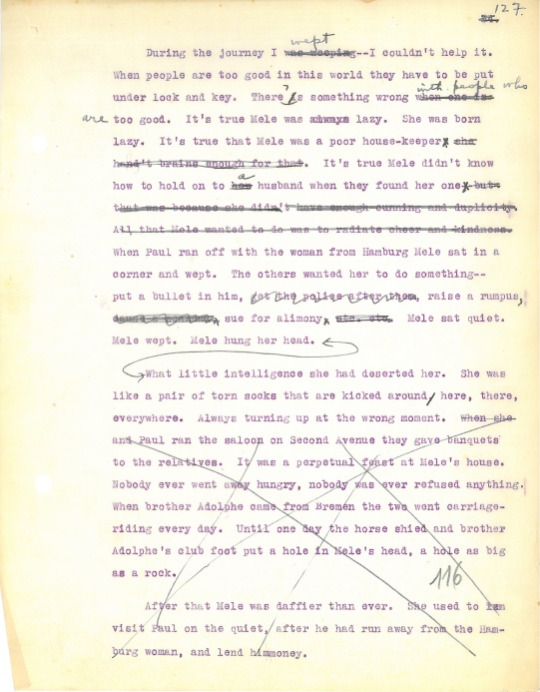

The typescript itself is 256 pages long and includes numerous excisions, authorial annotations, as well as copyeditor’s notes and setting instructions. One of the most exciting notations is Miller’s inscription on the title page to his friend David Edgar, painter and fellow American expatriate, who is known for rekindling Miller’s interest in arcane philosophies and religions. We asked Horowitz about this one-of-a-kind manuscript, Miller’s work in general, and what it’s like to deal in formerly banned books.

Literary Bennington: How did the manuscript of Henry Miller’s Black Spring come to you?

Glenn Horowitz: I found this typescript for Black Spring in a bric-a-brac sale at Sotheby’s earlier this year. Two times each year the auction houses mount sales of consigned material that they’ve accumulated over the previous months; these sales have no thematic threads and are, in many ways, a throwback to 19th and 20th century sales in which the various trades hoover up material that doesn’t come out of mature or curated collections. I saw the Miller and felt it could be a “sleeper”—an item overlooked by others. The estimate was $15,000-$20,000. I put in a bid of $50,000.00.

I understood that if I had to pony up the full 50 grand that with the buyer’s premium—the extortionist fee the big houses charge you for deigning to bid at their sales—I’d be in to the manuscript for $62,500, a price I felt comfortable dedicating to it. In the end I paid, all in, with surcharges, $40.000.00, which struck me as something of a bargain. However, since I bought it both Yale and the New York Public Library have turned it down for reasonable advances above cost. Maybe one man’s bargain is another man’s full retail.

The cover page of the Black Spring typescript

LB: Is there anything in particular that draws you to Miller’s work? What does he have to say to contemporary reader?

GH: For modern readers, Miller is both foundational and enduring. He let in light to corners that previously had been dark–and he did so with humor, an edge, and a raucous commitment to extending language and grammar. It’s always hard to understand how reputations will ice-skate through storms but my sense is that the essence of Miller’s work will continue to bedazzle readers for some additional generations. Maybe Dickens would be more widely read if he had his tongue just a bit higher into his cheek.

LB: The typescript has a plethora of Miller’s notes, revisions, and excisions of the text—is this kind of manuscript disappearing in the age of the personal computer?

GH: Only a blind person would be able to argue this point. The other night I had drinks with the writer David Lipsky [who attended Bennington in the mid-80s] and we got on to the subject of his compositional methodology. On the subject of his magical retelling of his four day road trip with David Foster Wallace in Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself, David said he had innumerable drafts—all in cyberspace. All of which, I assured him, contemporary curators can retrieve but there’s not, he sheepishly confessed, a single corrected typescript of any draft of the book. Of course his sheepishness was generated, I bet, by the fact that he was talking to a rare book dealer who was paying for the whiskey.

Miller’s corrections to the manuscript of Black Spring

LB: In his inscription to his friend David Edgar on the title page, Miller says “bastard death” brought them together. Do you know what he meant by this?

GH: Bastard Death was the name of the first work Henry Miller collaborated on with the expatriate writer Michael Fraenkel. I believe Edgar and Miller met through Fraenkel and their third collaborator Alfred Perles.

LB: Was there anything you uncovered about the friendship between Edgar and Miller after finding the manuscript? Do you consult scholars to explore this kind of background?

GH: We occasionally seek the input of scholars but when dealing with an individual item that has a very individual phenomenological life to it—a single typescript like Black Spring—and that we’re aiming at a research library we don’t pester the scholars with whom we’re close. But, as I said, when necessary we turn to pros for help. For example, Ed Mendelson can talk Auden to us until the last cigarette in the package has been smoked. Harold Bloom is helpful on Crane and Stevens. Joe Blotner was a tsunami of information on Faulkner. Alexander Waugh knows more about the work and books of his grandfather Evelyn than Evelyn did. I’ve been blessed by the willingness of scholars to glance at our work.

LB: Black Spring, along with Miller’s other works, was banned in the United States until 1961, yet it helped build Miller’s underground reputation. Is the market any stronger for books that have been banned?

GH: Banned books have a certain sex appeal. Joyce; Henry Miller; D.H.Lawrence, Ed Sanders and the Peace Eye Book Store and the Fuck You Press. And the Fat Lady hasn’t even begun to hum. But I think the boring answer is no. The market is best and hottest for great copies of major texts. Virginia Woolf is more valuable and sought after than D.H.Lawrence. Call it Sleep commands much more money than The Tropic of Cancer. And Ed Sanders seems better known as the founder of the Fugs than the publishing pirate who issued some of Pound’s Cantos in mimeographed editions on the Lower East Side. Great books fetch great prices regardless of how they entered the world.

LB: Do you have a favorite banned book?

GH: Special Operation Forces manual on eliminating ISIS maybe.