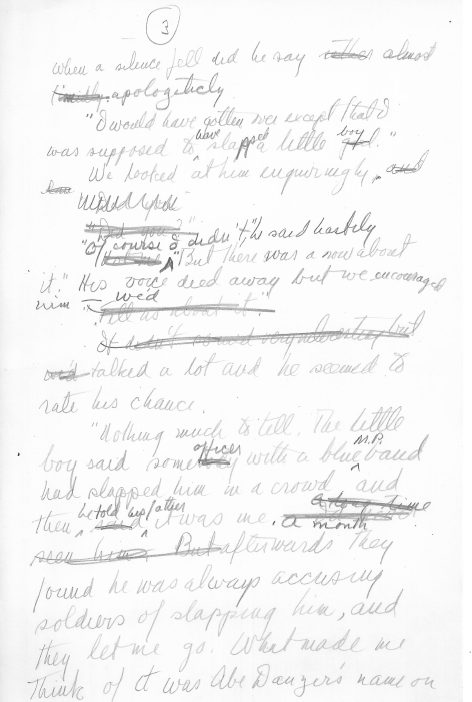

An emended manuscript of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s short story “I Never Got Over"

Glenn Horowitz, the famed Manhattan rare-book dealer and Bennington alumnus (class of ‘77), opens up in this interview about his journey from a childhood deprived of books and literary culture to a career as a pioneering representative of authors’ archives and estates. While at Bennington, Horowitz studied literature under the wing of Bernard Malamud (a member of the faculty from 1961-1985), and wrote, as he puts it, “a novel and a half.” With Malamud’s blessing, he was later able to merge his love for books with a penchant for business, and he has gone on to represent the estates of literary giants like Norman Mailer and David Foster Wallace (as well as Malamud himself) and the archives of Don DeLillo, Cormac McCarthy and Julia Alvarez.

In this Q&A with Literary Bennington, conducted over e-mail, Horowitz gives us the dish on a rare emended manuscript from F. Scott Fitzgerald written in the summer of 1936–just one of the treasures that Horowitz and his employees deal with every day.

We will check back in with Horowitz periodically for more Fetish Objects to feature on the blog.

Literary Bennington: Fitzgerald gave these manuscripts to his typist James B. Hurley in the summer of 1936 and they were sold at auction at Sotheby’s much later. How did they come to you?

Glenn Horowitz: These two states of the story–the handwritten manuscript and the corrected typescript–were purchased at Sotheby’s by a collector in the American South who recently parted with them. A colleague in London acquired them and I got the material from London.

LB: Is Fitzgerald one of the writers who you read while you were studying literature at Bennington? Did he make you want to be a writer yourself?

GH: I read Fitzgerald before Bennington; at Bennington; after Bennington. No, I don’t think any writer inspired me to the profession of authorship; probably had more to do with ego and a desire to be admired by pretty women.

LB: I know that you were at Bennington at the same time as Bernard Malamud. What was that like? Did you ever discuss life after Bennington with him? Was there a specific direction he wanted to direct your plan of study towards?

GH: Mr. Malamud was a tenacious, focused, hard-nosed man and teacher. He didn’t tolerate sloth or silliness, and if he was ticked off he could be stern, almost martial. I’ve reflected many times on how he perceived me when I was a student and though I believe he admired me for my dedication to writing–I graduated having written a novel and a half–I don’t believe he ever felt I had it in me to be a novelist.

That said, he kindly arranged after I’d graduated and settled in to NYC to introduce me to his agent Timothy Seldes, at Russell and Volkening, who took me, briefly, under his wing. But it soon became apparent to all involved that I wasn’t cut out for the writing life. But good things came of the stab I took. Mr. Malamud left instructions in his will that I should be involved with handling his Estate and Tim Seldes became a good friend and colleague. Through Tim I secured Nadine Gordimer’s archive and vast files of letters by Eudora Welty, Anne Tyler, Saul Bellow, and Bernard Malamud.

LB: What inspired you to go into the business of dealing in rare books and representing writer’s estates?

GH: In late 1977 I discovered that there was a world in which people bought and sold books for a premium. That revelation welded the two sides of my make up: the hungry student from a rural background who had consumed a vast amount of literature and history with the grandson and son of peddlers turned merchants and tradesman. I liked doing business, dealing and finagling, and I loved books: clearly I was blessed to figure out a way to conjoin those two interests.

I sold my first archive in 1982: the papers of the poet W.S. Merwin to the University of Illinois in Champagne-Urbana. I sold the papers for $185,000.00 and earned a $27,750.00 commission. Frankly, the size of the commission floored me. Plus I relished the details that were involved in crafting the transaction; the effort taxed me far more than buying and selling a single first edition did.

LB: You have had great luck in the past with James Joyce’s Ulysses. Do you consider it to be your most important dealing? Or is there another work that is dear to you for sentimental reasons?

GH: I’ve handled crucial Joyce material since I started in trade: manuscripts, letters, and inscribed books by F.D.R., Churchill, Virginia Woolf, and Joyce top my hit parade. And within Joyce’s canon I’ve bought and sold many exceptional copies of Ulysses. In fact, in 1999, in preparation for the new century, fresh millennium, I mounted an exhibition of inscribed first editions of Ulysses. Of the 38 recorded copies I exhibited 31, and published to commemorate the exhibition a sort of catalogue raisonne of inscribed first editions of Ulysses.

If I had to pick one other book that was especially close to me, for sentimental and financial reasons, I’d point to the suite of privately printed White House Christmas books F.D.R. produced during his Presidency: between 1933 and 1944 he designed and had the Government Printing Office produce 10 severely limited editions of his work. I relish those books.

LB: What’s it like to hold a manuscript like the Fitzgerald story in your hands? It’s amazing to see his own handwriting in pencil.

GH: I don’t mean to sound either spoiled or callous, but I’ve handled such an abundance of magical material that I’m jaded. I like handling the Fitzgerald manuscript a lot. I’d get great pleasure in handing it to someone who in turn hands me a credit card or a check.

LB: You have come across numerous manuscripts by now. Which writer do you think had the worst handwriting?

GH: Worst handwriting is easy: Malcolm Lowry. Drunk or sober–𐆑or in his case probably both at the same time–he made sentences that look like hieroglyphics.

LB: Have you ever gotten attached to manuscripts on a personal level and considered keeping certain ones for your own collection?

GH: I collect manuscripts and letters. I own major works by Joyce, Hemingway, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr., James Salter, Joseph Heller, Derek Walcott, and many others. I sometimes will fillet something out of my private collection if I’m buttering up a client or cobbling together a large transaction. I always regret removing something but I have children and private school is expensive. Something no one at Bennington would be aware of, I guess.

LB: What was your favorite book as a child? Did you ever get hold of that manuscript, or is there another manuscript or rare book you have been chasing for a long time?

GH: I wasn’t raised in a literary environment; there were virtually no books in my childhood home. Did that drive me as an adolescent to read voraciously at school? I’m sure some part of me understood that if I was going to get the hell off of the farm, so to speak, I needed to find a bridge to somewhere where language counted, thoughts registered, people disputed ideas.

I suspect one reason I focus on dealing with research institutions can be located in that paucity of bookish experiences in my youth. The first book that left me wide eyed was The Babe Ruth Story. Alas, two months before Ruth died in 1948, he gave the manuscript of that book to Yale. In fact, he handed it to the first baseman and captain of the Yale baseball team–George H. W. Bush.